The Knifonium, invented by high-end audio gear designer Jonte Knif might be one of the most interesting analog synthesizers on the market. This beautiful boutique hardware synthesizer, made from exhibition-grade walnut and ebony wood, is like a living, breathing instrument, powered by a whopping 26 vacuum tubes.

The original Knifonium synthesizers have been used by the likes of iconic composer Hans Zimmer and prolific electronic artist Hannes Bieger.

The original Knifonium synthesizers have been used by the likes of iconic composer Hans Zimmer and prolific electronic artist Hannes Bieger.

The plugin version faithfully recreates its sound while adding new features like multi-note polyphony, comprehensive effects rack, and powerful presets. It has quickly found fans among top-tier electronic artists including Junkie XL, edIT Beats of The Glitch Mob, and more.

The synth's designer, Jonte Knif, has a long history of making uncompromising elite-level pro audio gear under the Knif Audio brand name, including mastering quality compressors and EQs, tube preamps, and more.

SonicScoop's Justin Colletti talked to Jonte Knif on behalf of Plugin Alliance to find out more about his design philosophy, his approach, and what makes the Knifonium unique.

Jonte, thank you so much for joining us. I'm excited to talk about this piece with you. First off, I'd love to ask, in your own words, just what makes the Knifonium unique. Why is it so different from other synthesizers available on the market today?

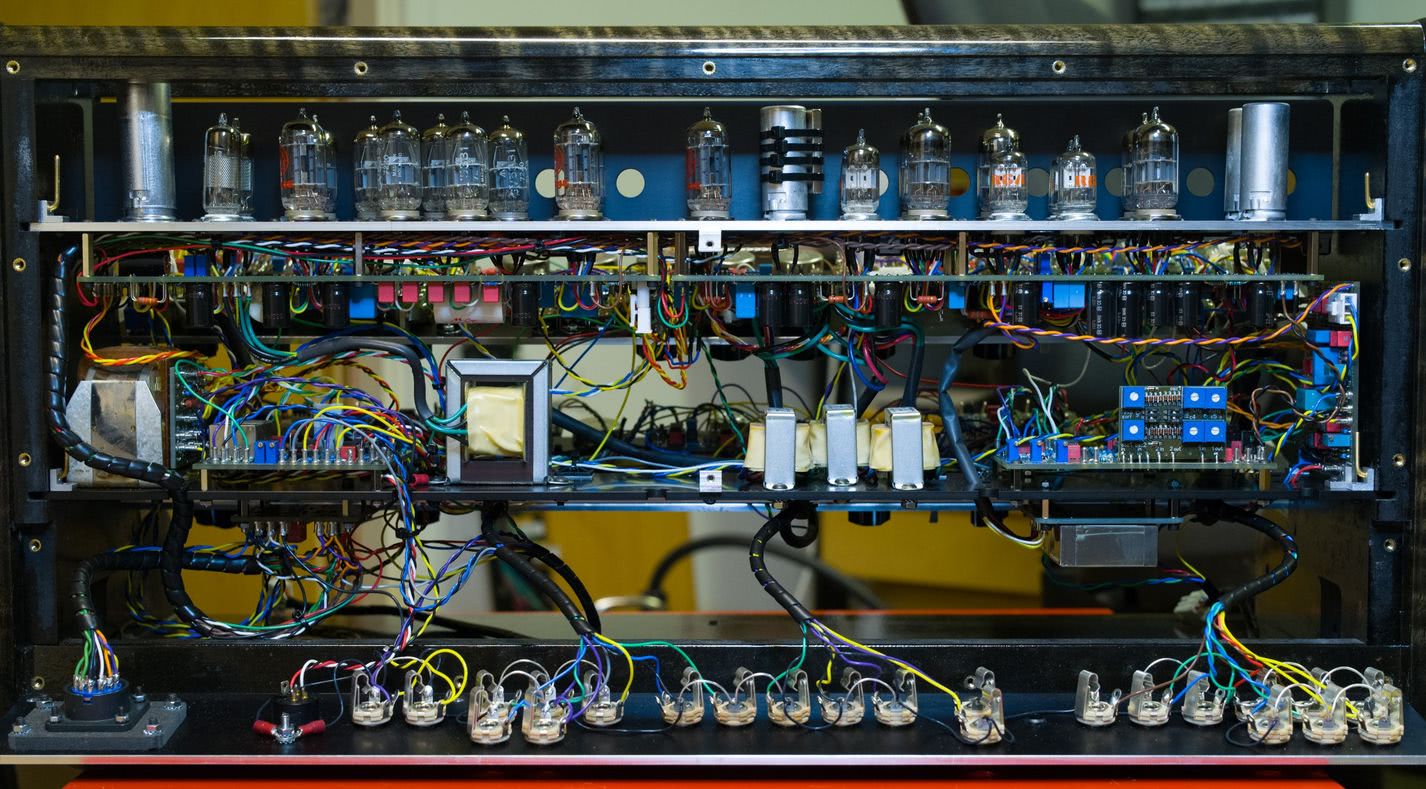

It's probably the most complete tube design out there. All of the audio signal path is built with tubes and transformers, and at proper high voltages. Only things like envelopes are made with solid state electronics.

What are some of the benefits of using tubes in a synthesizer design? Why would it be so important to you to design the whole synth around that kind of technology?

We are talking about mostly different ways to take advantage of the non-linearities of tubes: different kinds of distortion, overdrive, and so on.

When you start to overdrive the active part of the electronics—the tubes in this case—you get a different character than solid state.

Tubes have more mellow overdrive characteristics. And you have different tube types as well: triodes, pentodes, diodes. So, you have a lot of different tubes with different overdrive characteristics.

I also believe that in most tube electronics, the signal transformers are quite essential for the character. So, as they say, "the sound is in the iron."

So, aside from the Knifonium having tubes in it, what do you think makes this an attractive option for people out there who would be looking at other high-end analog synthesizers?

There's a lot of charm in the woodwork, the very responsive keyboard, which uses real materials like ebony. It has aftertouch and velocity, and a very nice joystick. It's a very live performance capable synth. It's easy to patch, and there are a lot of interesting patching options, different feedbacks, modulations everywhere, so it's very versatile.

I guess one of the limitations of making a gorgeous, super high-end tube synthesizer is you can't make a ton of them. How many of these have been made so far? And how many more can we expect to be made?

So far, only 22 have ever been made. We can expect to have at least one more batch. And, after that, maybe a few more. Who knows? So far, it's been from 6 to 8 units per batch, once every two years.

When I read the headline about the Knifonium, it says that "Knifonium is a 26-tube monophonic synthesizer with two oscillators, a fourth-order ladder filter, and a ring modulator." What is the importance of having two oscillators? What is a fourth-order ladder filter, and what's a ring modulator?

So, one oscillator only would be pretty boring, because with two oscillators you can have them slightly in a different tune, or you can lock them together with the oscillator sync effect. And you also need two oscillators to use the ring modulator.

The ladder filter is a very traditional part (of a subtractive synthesizer). It's the most important sound sculpting part of most synths, and in this case, it's done with tubes—it's a full tube unit.

The basic idea is the same as the original Moog ladder filter. And a ring modulator is a signal operator, which does multiplication. So, you take one waveform and multiplicate it with another waveform. And this creates a lot of interesting spectral combinations, sidebands, and sum and difference frequencies. So, you can create complex aharmonic structures, or you can create harmonic structures with very interesting spectra.

What types of sounds do you think that the Knifonium does particularly well?

Well, I can only talk from my own perspective, of course, but I do like the distorted sounds a lot. The filter, output amplifier, ring modulator, and mixer, all distort in a very beautiful way, and it's very organic.

It's not like adding a distortion box to a sound. It's an interaction. For example, in the filter, it changes with the way you adjust the frequency and Q value of the filter. It's very organic.

For me, it's been a great joy that the basic sound quality of Knifonium fits very well with acoustic instruments. I've played with friends, and also there is a concerto for California for Knifonium and chamber orchestra, in which I played the solo part. And it just works so well. It would be a totally different thing with a modern, cleaner, more "pure" sounding synth. It would no longer meld in, in the acoustic textures.

You've actually made other types of keyboards in the past, and you make to this day, a lot of high-end tubes and non-tube mastering, mixing, and recording gear. Can you tell us a little bit about your background and what your other interests have been in audio, and what are some of the other designs you've been particularly proud of?

]My background is a bit schizophrenic. I studied harpsichord at the Sibelius Academy for many, many years. But apart from the music study, I've always been very interested in electronics. I didn't do much with it before I got into the music technology department at the Sibelius Academy. I first built some tube amplifiers for home use, and some loudspeakers, some nice ribbon dipole loudspeakers, even commercially for a while. But then I got very interested in studio gear after I got more into pro audio.

Before that, when I was still playing a lot, I used to build some of the instruments myself, like a hammer dulcimer, which I played a lot, and then harpsichords—though not totally without help. I designed my own models, and I was always very interested in making things which produce beautiful sounds, and which can be used for making music in real time.

My sort of master thesis at the music technology department was an instrument. An electric clavichord—or let's say electro-acoustic clavichord because it has a soundboard and acoustic sound too. I love this instrument because it's so expressive. You can make vibrato, and you can make bends, and you can use different kinds of alternative playing techniques.

I remember one of the things you said to me in our initial conversation was that since you were so interested in designing a synthesizer for live performance, that you wanted to avoid making it into a "chaos machine". You wanted to make it so easy to get very musical sounds out of it.

Yes. Although you do have the option to make things go out of hand, because, for example, with the feedback option, you can feed signal from the output to different locations in the signal path. With that, you get really, really unpredictable sounds. When you add modulations and sample and hold and LFO with good taste.

You can get sort of semi-chaotic patches, which are very enjoyable also. But I was not happy with the idea that that would be the only thing you can do with this. You have to be able to do controllable things. It had to be well-tuned to play traditional harmonic music as well.

What is the process of building one of these?

It's usually been about four or five people taking part. The woodwork is done by a friend of mine, an industrial designer who polished my original design a lot. Here at Knif Audio premises, we do all the electronic stuff, and I adjust and balance the keyboards, build the joysticks, and these sorts of things.

I currently have two employees, and they are mostly responsible for all the soldering and, very roughly, it's about 60 to 70 hours of woodwork per instrument, and let's say 80 to 100 hours of soldering. And then it's about 10 to 15 hours finishing, tuning, testing, testing, tuning, testing, changing tubes, matching tubes, and so on.

You recently worked with Plugin Alliance and the engineers from Brainworx to recreate this synthesizer as a software emulation. What was that process like? And what did you think of the result? Is there anything you were pleasantly surprised by or came out particularly well in the emulation?

The process of working with them was extremely easy and pleasant. I didn't have to do much. I provided an instrument for them, of course, all the schematics and then answered some questions when they found something unexpected.

Just for my own interest, I asked how they model things, and it was very interesting to hear what kind of dedication is involved. Most of the time, we didn't have to communicate much. When they finally had the first beta version, I tested it and gave some feedback, and also played it for many hours, just for my own pleasure because it was a lot of fun.

What I think about the result? The emulation of the tubes is extremely credible, actually. The mixer and output amplifier and all the feedback loops and ring modulator, they are very, very close to the hardware. So yes, it's a success, I would say. Of course, there will be some differences, but in no way one could say that they missed anything.

I'm excited to try this out and put it through its paces. Pretty much anything that this can do, at least in theory, the plugin should be able to do. The full range of controls are there, the patching options are there.

Yes. You can really do everything with it. Even the chaotic things with feedback, they sounded just like they should.

Thank you so much for joining us today. It's been an absolute pleasure talking to you.

Thank you. It's been a pleasure.